This week saw the debut of broadband “nutrition labels” to help you understand what you’re paying for when you buy into a high-speed internet plan. You can find them posted in stores or online from companies like T-Mobile or Comcast, and any wired or wireless provider with over 100,000 customers is required to post them.

This got me thinking about the state of high-speed internet in North America — specifically how some of the biggest issues are still the same as they were years ago.

There are two real problems: unavailability and overcrowding. I’m sure industry experts have fancy names for them, but in the end, many people have limited or no access to high-speed internet because of these issues.

In rural areas, there just isn’t enough to go around. It costs a lot of money to bring service to an area, and service providers are reluctant to make it happen without enough customers to pay for it (and then provide huge profits). You have to remember that businesses are in it to get rich, not provide a service.

The flip side is in places where there are too many people. Fast, reliable service has a user cap, and when it’s exceeded, the quality starts to go downhill. Usually, it’s just an inconvenience at certain times of the day or on certain days, but internet providers are like airlines and will sell, sell, sell, regardless of actual capacity.

Nutrition labels aren’t going to fix this. Maybe nothing can fix this. We can’t let that stop us from demanding more from the companies that send us a hefty bill every month, though.

Rural areas are still screwed

In rural parts of North America, there are two types of internet service — poor and none. In 2024, it’s almost impossible to take advantage of the technology age or the latest new phone when internet is in the state it’s in.

It is getting better, but just barely. Take where I live, for example. I’m in one of those weird areas where rural isn’t really rural — I live in the mountains 43 miles from Washington, DC. It’s a cool place to live but it used to be the place where the internet went to die.

Up until a few years ago, “high-speed” just wasn’t a thing. In 2012, the Obama administration started an initiative to make high-speed internet access along all federal highways feasible. That has trickled away from the highway, and now I have 5G wireless and fiber internet at the same address that I had to pay for Comcast to bring cable to in 2007.

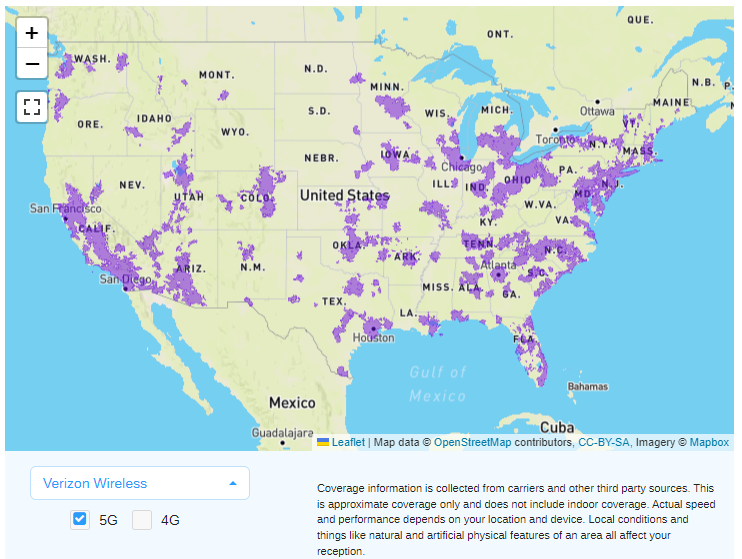

Not everyone, especially those away from any major city, is so lucky. There are areas with no internet service of any kind, but those are few and far between. The issue becomes clear when you look for high-speed coverage.

Companies like Starlink make things better, but Starlink is expensive and requires a lot of maintenance. It’s not like DirecTV, where it just works.

I understand the problem — there just aren’t enough people to justify it. But this is not what we were led to believe high-speed wireless would be like in 2024.

Too many people can be just as bad

Everyone has heard stories about how bad connectivity is at a place like Google I/O or a New York Giants football game. When you cram that many people into one place at one time, it’s very difficult to provide service to them all.

The thing is, it doesn’t take a major tech conference or football game to make service bad. All it takes is just one user beyond what the total capacity can handle.

I’ll use another anecdotal example here. I have some friends who live in DC, and at lunchtime through the week and all day Saturday and Sunday, their service slows to a crawl. This happens because everyone checks their phone at lunch and on the weekend a million extra people are in DC to see the sights.

AT&T provided the infrastructure based on the people who actually live there. Quadruple that number, and things get bad. This can made better using portable cell towers for things like ball games or during DC’s Cherry Blossom Festival when the crowds are huge, so more infrastructure is the fix.

Nutrition labels are fine for telling how the service we’re paying for is supposed to work. The only way to fix anything is to throw money at the problem, though.

You probably don’t see these issues — I admit they are fringe cases. However, they are the same fringe cases that have affected the same users for a decade. Before we move on to 6G, they must be addressed, or North America will fall further behind when it comes to high-speed connectivity.