Sunday Runday

In this weekly column, Android Central Wearables Editor Michael Hicks talks about the world of wearables, apps, and fitness tech related to running and health, in his quest to get faster and more fit.

The best smartwatches and smart rings act like a daily, mobile doctor’s appointment, taking continuous readings and warning you if something’s off. But when something is off, and it’s not something easily fixable, it can become a source of futile anxiety.

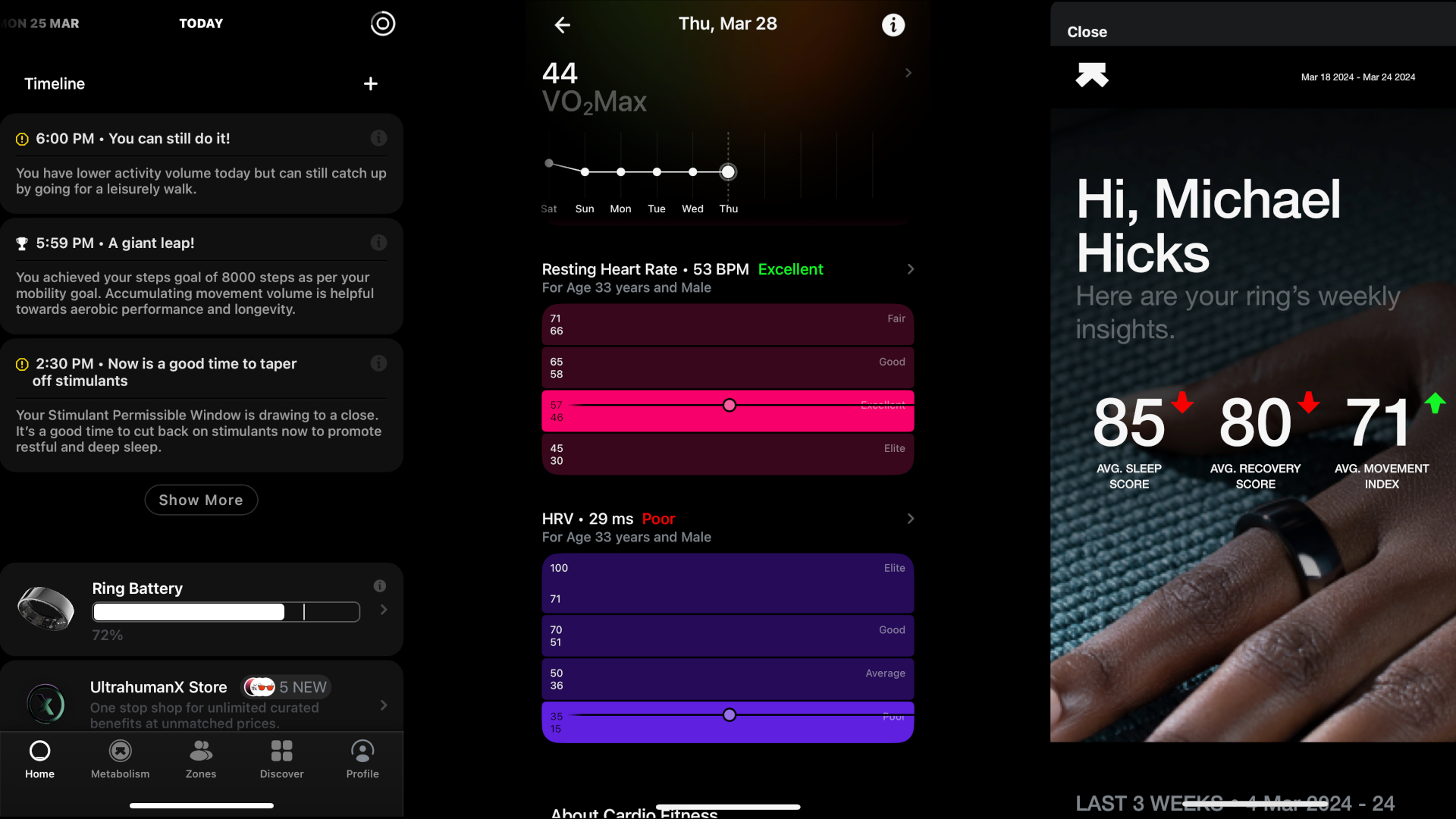

I’m a competitive person. Whether it’s training to get an “excellent” VO2 Max for my age or seeing how my resting heart rate (RHR) compares to others, I like to set lofty goals to motivate myself to get healthier and live longer.

Companion apps for smartwatches and smart rings play into this dynamic. My Ultrahuman Ring Air directly compares my nightly results against the “Community Average” or “Top 10 percentile average,” so you know if you’re “Superior” or “Poor” in certain areas.

Other apps ignore the masses and focus on your baseline and any deviations, good or bad. That’s a better approach, but even then, AI-backed apps like Samsung Health may encourage you to set improvement goals and praise you for beating your past self in areas like RHR or weight — or shame you for slacking off.

But what if you can’t improve? What if, like me, you have a subpar heart rate variability (HRV) for your age, signaling possible long-term issues, and nothing seems to change that? It turns out that impotence in the face of bad data can make you spiral a bit.

Be careful what you wish for

In a previous column, I explained why I hate wearing smartwatches to bed: they’re uncomfortably distracting, either waking me up by digging into my skin or coming loose and giving me inaccurate results.

In other words, wearing smartwatches at night stressed me out, so I thought it was a temporary concern when they registered poor heart rate variability.

Then I started wearing my Ultrahuman and could finally get consistent sleep data. It gave me optimal ratings in most categories for sleep, blood oxygen, and restoration. But it showed I had “poor” HRV and slow HR drop for my age group on a nightly basis, whether or not I’d worked out or felt any particular stress.

Why does HRV matter? Your heartbeat has a natural irregular rhythm when you’re at rest. If your autonomic nervous system (ANS) signals your brain that something is wrong, whether due to physical or mental stimuli, it reduces the variability between beats, making your heartbeat more like a metronome.

Factors like “stress, poor sleep, unhealthy diet…and lack of exercise” can lead to lower HRV, says the Harvard Medical School. And the Cleveland Clinic suggests it can signal “current or future health problems,” from “heart conditions” to anxiety and depression.

What these sources don’t properly explain is that HRV is highly individual. Healthy people can have below-average HRV even with consistent sleep, normal diet and happiness, and regular exercise. It’s not something you can fix or should compare to others, only something to track for irregularities from your norm.

But when smartwatches and smart rings make health a game and tell you to try and beat the averages, it’s hard to accept it when a simple Google search shows that your health data is subpar and you’re “losing” the game.

In this case, seeing HRV scores that suggested I had an anxiety disorder or warning signs of future heart problems was a fantastic way to give me an anxiety disorder. And based on all the Reddit threads from healthy people freaking out about their low HRVs, I’m not alone.

Sometimes the game is rigged

Since Ultrahuman gave me concrete evidence of a possible problem, I went into competitive “fix this” mode. Since low HRVs are associated with poor physical health and excess alcohol, I spent 2024 losing weight, cutting back on drinking, and running and rucking a healthy amount every month.

My annual checkup and blood work this year showed healthy results and better blood pressure than in 2023. But even as I got healthier, my HRV score consistently remained in the mid-to-high 20s. This week, my Pixel Watch 3 measured me at 29ms, pretty close to my norm, while my Garmin Fenix 8 had me as high as 36ms.

For context, regular runners with high VO2 Max might see an HRV status closer to 70–100, while WHOOP says its HRV average for people in their mid-30s is 60.

Since physical changes didn’t seem to help, I tried going to therapy to address possible mental stressors. My new therapist told me that my first step should be to stop wearing smart rings because the data wasn’t helping me.

After a few sessions, she said it was clear I didn’t need therapy, so long as I reminded myself that my HRV score doesn’t matter if I’m otherwise healthy and to try relaxing more.

It’s hard following that advice — especially with a job testing new watches and rings every week — but I’m trying.

Brands like Garmin and Fitbit show me with a lower Daily Readiness or Body Battery than others getting the same amount of sleep because lower HRV means a worse “recharge” or recovery. I used to stress about that; now, I just try to get more sleep.

Data is a double-edged sword

Despite my HRV ordeal this year, I still believe watch and ring health data is a net positive for the world.

Right now they can catch irregular heart rhythm that signals serious heart issues or warning signs for sleep apnea. In the future, they could warn you of excess sweat loss during extreme heat, high blood glucose levels, or other life-threatening problems with clinical accuracy — especially if the Masimo-Wear OS partnership works out.

But if you start tracking your health data, be prepared not to like everything you see. Some stats can be improved with time, but it’s a lot of pressure and a negative source of motivation. And as you get older, certain stats will naturally get worse no matter what you do.

My advice? Don’t be afraid to take your smartwatch or smart ring off for sleep data once you’ve been warned of a problem, until you’re ready to cope with your “poor” results without letting it overwhelm you.