On April 25th, the FCC voted along party lines to restore net neutrality. This is being framed as the best thing that could happen or yet another blunder by the current administration, depending on which talking head you’re listening to and what organization they represent. But what does it all really mean for regular folks like us?

Android & Chill

One of the web’s longest-running tech columns, Android & Chill is your Saturday discussion of Android, Google, and all things tech.

To figure it all out, you need to know what net neutrality is, it’s history, and how the U.S. compares with the rest of the world when it comes to internet access and usage.

What is net neutrality?

In a nutshell, net neutrality means that internet traffic is all treated the same. It doesn’t matter where the data comes from or who it’s going to; it flows across the internet with no interference or restriction. The government of New York lays it out nicely:

Net neutrality refers to the principle that the companies that deliver internet service to your home, business, and mobile phone, such as AT&T, Comcast, and Charter (often referred to as internet service providers, ISPs, or broadband providers), should not discriminate among content on the internet. According to this principle, broadband providers cannot block, slow down, or charge to prioritize certain content; rather, they must treat all content equally. This prevents your broadband provider from acting as a gatekeeper and blocking internet content or applications offered by their competitors or from playing favorites among competing services vying for your attention.

A more nuanced take is looking back a few years when service providers were fighting with Netflix.

Back in 2013, Comcast demanded Netflix pay them extra because so many subscribers were using the service. Netflix refused, so Comcast artificially throttled all Netflix streams that used its network, making them unbearably slow.

As a consumer, the only thing you would have noticed is that Netflix was terrible while other streaming platforms — like the ones offered by NBC (Comcast’s parent company) — were great. So, rather than take the hit to its reputation, Netflix paid them off.

When this happened, customers almost immediately noticed a vast improvement in quality when it came to Netflix streaming. Comcast added no infrastructure to make this happen; it just allowed Netflix data to be treated the same as any other data.

Net neutrality makes it illegal for Comcast to use these tactics against Netflix or for companies like Time Warner to use them against NBC because consumers are negatively affected when they do. Data is data, and service providers should only be a pipeline to deliver it.

This isn’t automatically a bad thing. Comcast should negotiate for more money from Netflix if it’s causing adverse network conditions. The issue is with Comcast’s tactics because they made consumers suffer.

Net neutrality opponents say unbiased traffic laws are unnecessary and that more transparency from service providers would allow customers to choose which provider worked best for them.

That may be the case for some people, but not everyone has a choice when it comes to broadband providers. In many rural areas, the only choice is to pay the lone provider that services them or not have internet. And in some cases, there is no choice at all.

How did we get here?

It’s easy to frame this as an Obama v. Trump v. Biden fight, but it’s really all at the feet of the FCC.

The FCC’s attempt to guide service providers and use a light touch when it comes to regulation over the years was a sound choice on paper. In reality, it failed.

In 2005, the FCC classified service providers as information services and not common carriers like telephone service providers. Fast-forward to 2010, when net neutrality was first introduced as the Open Internet Order, and the ruling was immediately challenged by broadband providers.

The broadband providers won. Most famously, the case of Verizon v. FCC saw the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals vacate the portions of the Open Internet Order that deal with blocking or throttling specific internet services. This is because the FCC only has the power to enforce such measures when they apply to common carriers, not information services.

When providers were classified as common carriers in 2015, it was settled, and then in 2017, the changes were rolled back. Once again, there were no restrictions placed on data providers.

A common carrier is a company regulated by the government to provide a service with no discrimination based on its content. In exchange, these companies are immune from liability for any of the content it has carried. You can’t sue the phone company because one criminal called another criminal and talked about committing crimes against you, for example.

Airlines, railroads, and traditional taxi and carriage companies are common carriers. Some telecommunications services are classified as such, but data providers like broadband ISPs were not.

Why this matters

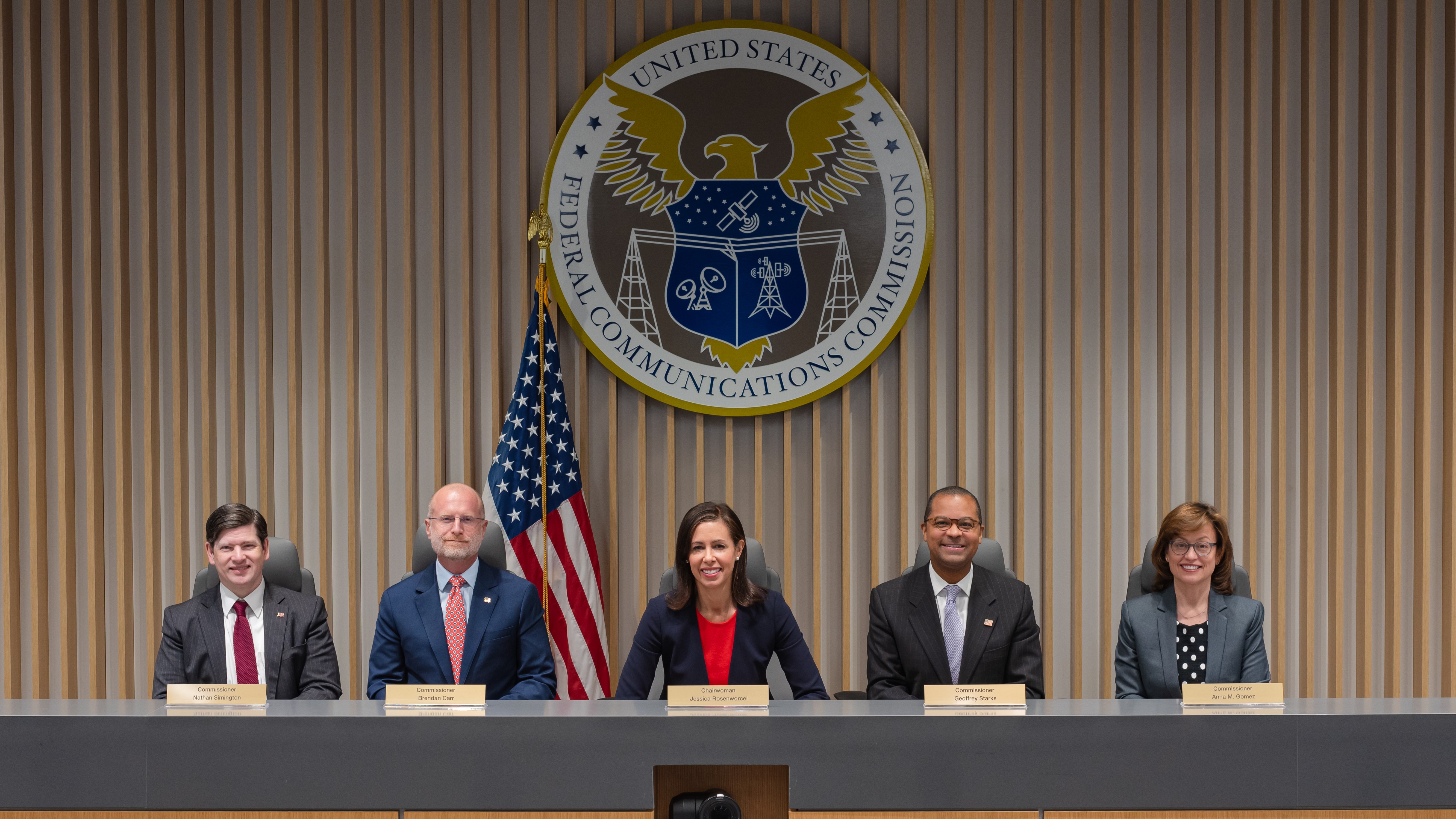

With the recent ruling, broadband providers are classified as a normal telecommunications service under Title II just like a traditional phone company, and are no longer permitted to discriminate based on content.

This means all data transfer is treated the same, no matter where it originates, and service providers are closer to being a dumb pipe that simply carries the content. The pros of this decision are easy to understand — no company is slowing down your access to information or entertainment as leverage to make money. You paid the same for access when data was purposefully slowed down, so this is a win for consumers.

It’s also a win for education, medical treatment for veterans, first responder’s ability to operate, and families who live across the country or abroad according to FCC Commissioner Anna Gomez.

Opponents, like Commissioner Brendan Carr, do make a valid point. Don’t get sidetracked by the theater of blaming President Obama and comparing the restoration of Title II classification to student loan debt relief. That’s become the norm, and it’s included to satisfy a small portion of the electorate. Read the dissent, and you’ll see that Carr says this will mean higher costs for consumers.

He’s right. The Comcasts and Verizons of the world will charge us more because they aren’t able to extort money from Netflix or Amazon. The FCC is charged to look out for U.S. consumers, and an act that will raise prices seems to go against that.

It could also be said that the year over year rate increases we pay for internet services and entertainment was because companies like Netflix and Amazon had to pay more in order to be treated equally, so it all evens out. All the companies involved will pass costs along to consumers whenever they can.

We each have to form our own opinion about net neutrality. Every person who writes about it or does a newscast on the subject has his or her own opinion, and their content will reflect that.

This article reflects my opinion that treating broadband data providers as a common carrier is a necessity because of my own circumstances. I rarely think the best first course of action to solve a problem is government oversight. Slow-moving decisions mired in red tape can make things worse and often do. In this case, I think it’s worth the risk.

You have your own set of circumstances and will form your own opinion.